Europeans are rapidly reforesting cities with tiny, dense patches of native forest with a Japanese method that makes them grow 10 times faster than normal

Japan’s most famous botanist Akira Miyawaki has inspired a fast-growing tiny forest revolution in Asia and now in Europe.

The goal is to restore a patchwork of native forests throughout urban areas, where they have almost entirely disappeared.

You’ve heard of ‘food deserts‘ in densely populated cities… hand in hand with this problem are ‘forest deserts.’

The vast sprawl of human development around the globe has disconnected wildlife from their natural habitats and hunting and grazing ranges so much that an alarming number of species is going extinct.

As we learn that we too are a species dependent on forests, humans around the planet are racing to reforest it.

And we’re learning that it’s important to do that not in some far away place that we have to drive hours to visit, but right in our own backyards… and on every square foot of unoccupied city space.

Thus, the rise of tiny forests.

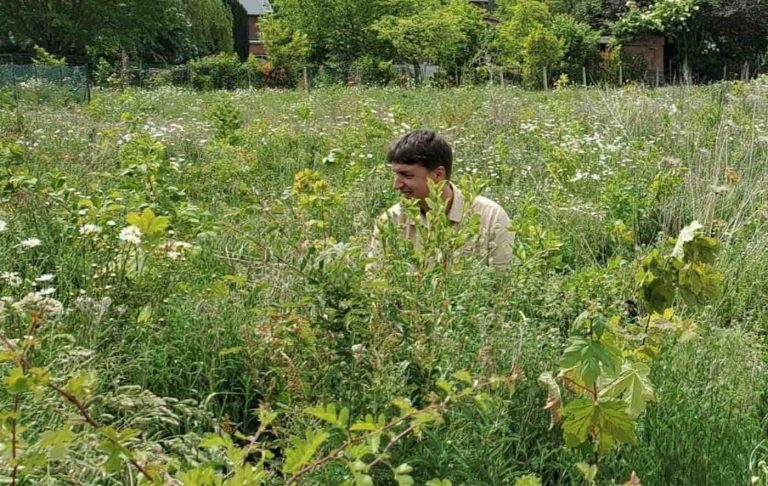

Using the Miyawaki method, volunteers are planting a densely packed, diverse variety of native tree and plants in small chunks, wherever they can find open space.

Though many of these mini-forests are no bigger than tennis courts, they are extremely productive chock full of diverse species of wildlife.

Miyazaki’s tiny forests grow 10 times faster and become 30 times denser and 100 times more biodiverse than those planted by conventional methods.

That’s because saplings are planted very close together, three per square meter, using a wide variety of native species (ideally 30 or more) adapted to local conditions.

Plants of several heights are selected to achieve a fast-growing protective canopy layer (that helps create more rainfall) along with a dense understory and middle layer.

The forests must be watered diligently until the canopy layer forms, at which point, the forest will mature in record time.

Though small, they support a far greater number and variety of wildlife than much larger non-native forests that have been planted to replace deforested areas over the last century or two.

The idea is “to create wildlife corridors through contiguous ribbons of mini-forest.” Wildlife scientist Eric Dinerstein tells The Guardian.

Migratory songbirds are one species that will greatly benefit from such efforts, he notes.

“Songbirds are made from caterpillars and adult insects, and even small pockets of forests, if planted with native species, could become a nutritious fast-food fly-in site for hungry birds.”

More than 100 Miyawaki-style forests have been planted in the Netherlands since 2015, with plans to more than double that number by 2022. At least 40 such forests have been planted in France and Belgium.

After just 3 years, a tiny, 300-tree forest in Belgium is already 10 feet tall with a thick layer of humus developed below, says founder of Urban Forests Nicolas de Brabandère.

Natural, biodiverse forests can store 40 times more carbon than single-species plantations, making them essential in the fight against climate change.

And the Miyawaki forests are designed to regenerate land in far less time than the 70-plus years it takes a forest to recover on its own.