As our understanding of the minds of our fellow species improves, will we increasingly look back at the way we have treated them in horror and repulsion?

by Jeremy Hance · Photographs by Karine Aigner

Water streams off the edges of her giant ears, runs in rivulets down the wrinkles of her slate-grey skin. She presses her whole head into the hose’s force, the spray welling into her mouth. As she drinks, she rubs her skin against the steel fence, her eyelids drooping luxuriously, her trunk relaxing. If ever I’ve seen a captive elephant happy, it’s Flora this morning.

There are no people laughing or pointing here at the Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee. There are no infants crying, no children arguing. The public are not allowed into the sanctuary, whose unofficial motto is, “Allow elephants to be elephants”: give them the freedom of choice, the freedom of large areas to explore, the freedom from human gawkers (apart from via the online elecams) while still providing the kind of care that comes with a zoo.

In fact, few things are required of the 10 pachyderms here. They can sleep in the barn or they can spend the night among the pine-covered hills. They can stay in the shade or lounge in the sun. They can wander together for company like elephants in the wild or take off on a solo sojourn. They can chase turkeys or trumpet at deer. They can take a dust bath, roll in a mud wallow, or be sprayed by a keeper, as Flora chose on this day when the temperature hits 34C (93.2F).

“I don’t think we will ever get away from elephants in captivity,” Stephanie DeYoung, the director of elephant husbandry, tells me. “But is it time to change how we keep them in captivity?”

- The Elephant Sanctuary spreads over 2,700 rolling acres.

Beaten, starved, shackled

Watching her now, it’s hard to imagine Flora – a female African elephant, the largest and arguably most regal terrestrial animal on the planet – dressed up in a silly costume performing in a one-elephant act for 18 years. But that was her life before.

We are, as a species, generally fascinated by elephants. “We see the qualities and characteristics in elephants that we aspire to have ourselves,” says Patricia Sims, the co-founder of World Elephant Day. “Empathy, enduring family bonds, cooperation, intelligence, long memories, taking care of their environment – to name just a few.”

Some extraordinary scientific studies in the last few years have revealed just how intelligent they are. They can recognise themselves in a mirror, found scientists in 2006, one of only a few species that do this. They can have an “aha” moment to solve a puzzle, showed researchers in 2011, by witnessing a young elephant in the National zoo in Washington DC who would move a block wherever she needed it to reach food. We even know now that what makes captive elephants happy is not the size of their pen, but whether they live with other elephants, thanks to a landmark collection of papers in the scientific journal PLOS ONE last year

But our desire to be close to these incredible creatures has led us down some ugly paths. We have ridden them, dressed them up in ridiculous attire, beaten them, starved them, and slaughtered them en masse. Today tens of thousands live shackled in prisons of our making.

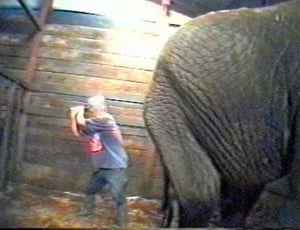

- A video still from a report that was shown during the trial of circus trainer Mary Chipperfield, who was convicted in 1999 on 12 counts of animal cruelty.

Elephants are still gussied up to decorate weddings in India; in Sri Lanka they are locked in religious sites as living (but suffering) embodiments of a god; in Africa tourists ride trained elephants to see wild ones; in south-east Asia elephants are used to log the very forests they once called home; and worldwide elephants are still forced to perform silly tricks in circuses and zoos, tricks they are trained to do by brutalising methods, often using a bullhook, a large, sharp, medieval-looking instrument used to create pain in an elephant’s sensitive spots.

When I ask ecologist and author of Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, Carl Safina, if he believes elephants are intelligent and conscious, he says that there is “zero” evidence that such animals are not conscious, while there is multiple lines of evidence – both physically and behaviourally – that they are.

So what are the implications of this? Besides their own particular form of consciousness, elephants have spectacularly good memories. Can they remember abuse and pain? Could some elephants even be described as traumatised? There have certainly been episodes that would seem to indicate this. In 1994, for example, a female African elephant named Tyke crushed her trainer to death in front of a circus audience in Honolulu. She escaped the tent and ran through the city streets for a half hour before police officers brought her down in a hail of 86 bullets. Like all circus elephants, she’d spent her life chained up, transported in trucks and beaten to perform. The only freedom she’d known was when she’d escape – and she’d done so twice before. (The 2013 documentary Blackfish, about a killer whale, Tilikum, appears to tell a very similar story about another of the earth’s largest mammals.)

- Sukari in her enclosure

Over and over again, staff at the Tennessee sanctuary tell me that “elephants never kill anyone accidentally”. Like humans, they can snap. Constant beatings, solitary confinement, being chained to the floor: all this can understandably push any elephant to the brink – and some will retaliate.

In her book Elephants on the Edge, Gay A Bradshaw argues that elephants – both wild and captive – can suffer psychological traumas, leading them to become more unpredictable and violent. “When elephants lose their homes and families, are subjected to mass killing, and are captured and incarcerated in zoos, they breakdown mentally and culturally and exhibit symptoms found in human prisoners and victims of genocide,” Bradshaw said in an interview with Scientific American.

In her book, Bradshaw describes an experiment where the symptoms of an elephant were sent to five mental health officials – who had no knowledge that they were diagnosing an elephant and not a human – but all of whom diagnosed the individual with PTSD.

As our understanding of the minds of our fellow species improves, will we increasingly look back at the way we have treated them in horror and repulsion?

- Shirley’s right ear was scarred when she was on a ship that caught fire and sank.

Unloosening the chains

The impact of our changing understanding of elephant psychology has already been profound. Perhaps the most astounding change is at circuses. Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey, arguably the world’s most famous circuses, stopped using elephants last year – and then closed for good this May after 146 years. Britain’s last circus elephant, Anne, was rescued in 2011 after the Daily Mail revealed she was being viciously abused. Twenty countries have banned the use of elephants in circuses. Even India has banned elephants in both circuses and zoos – though the process of retiring the elephants is gradual.

“The day’s gone by of putting an animal in a cage and calling it entertainment. I think more and more people realise that is ridiculous,” says DeYoung.

Life in zoos is generally not as abusive for elephants as in circuses. Zoo elephants are not travelling overland on a weekly basis, are not usually chained up for days to weeks to years on end, and are not usually forced to perform tricks day in and day out.

But there have been enormous changes here too. Recognising the social needs of elephants, the US’s Association for Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) now requires that any accredited zoo must have at least three female elephants, two males or three mixed genders in order to make sure elephants have peers although facilities can apply for an expectation. (There has been less progress on space: a creature known to roam hundreds to thousands of square kilometres in the wild gets as little as 500 square metres of outside space in a zoo.)

The best zoos are changing concrete cages to natural environments, adding more enrichment and taking their elephants for daily walks to increase exercise. Today, 43 zoos are members of the Elephant Welfare Initiative, which tracks real-time data on their pachyderms, all in an effort to improve conditions. And many elephant keepers now have behavioural backgrounds, an acknowledgement of the species’ deep psychological needs, explains Otto Fad, an animal behaviour and welfare specialist. “All of us ‘elephant geeks’ are paying attention,” he says.

- Adult elephants and a calf chained in an indoor enclosure at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, US in 1989. Photograph: Scott McKiernan/Zuma/Alamy

But progress is slow, and patchy. China is buying up wild elephants from Africa, and Chinese zoos are hardly known for humane conditions. Eyewitnesses say zoos there are forcing elephants to do unnatural tricks to entertain visitors, much like circuses. Even in Europe controversy remains: In April, Peta released footage of keepers at the Hanover zoo in Germany using a bullhook and whip to train juvenile elephants to perform tricks. The European Association of Zoos and Aquariums and the AZA both still allow the use of bullhooks.

And then there are the 15,000 to 20,000 elephants around the world that still spend their lives in chains. “Harsh,” is how Carol Buckley, the head of Elephant Aid International, describes conditions in Asia. “With little exception, they live in chains when not being dominated by their mahout to perform.” The mahouts “suffer equally … [Both] live in squalor, deprived of the most basic needs.” In Indonesia, activists have photographed an elephant in a zoo that lives alone with its feet tied together by a chain. It can’t move a single step.

So, what to do? We can’t just open the pen doors and unloosen all the chains.

If only they could all go and live in the sanctuary.

- Ronnie (on the left) and Sissy in their enclosures. Out of shot are their companions. All are free to roam in 100s of acres.

“They are allowed to express themselves”

No institution is perfect. Founded in 1995, the 2,700-acre sanctuary – North America’s only one dedicated solely to elephants – has seen its own set of tragedies and challenges, none worse than when a keeper was killed in 2006 by an Asian elephant.

But it is a genuine sanctuary for once abused elephants, tended to by the most devoted of staff, who practise a form of elephant care known as “protected contact” or PC, a type of training invented in the 1990s by San Diego zoo. This is in opposition to what’s called free contact, which generally depends on bullhooks and punishment. Keeper Kristy Sands Eaker says PC is about “mutual respect”, and about positive reinforcement – rewards for good behaviour – rather than punishment. “They know we are not going to enter their space … They are allowed to express themselves … if they do not want to participate in something … they can react and there’s no punishment for that.”

At the same time, the animals are not romanticised: elephants and keepers are always separated by a steel barrier; there are always at least two keepers working with an elephant, and all are aware they are dealing with four-tonne animals capable of killing with a single strike of its trunk.

The sanctuary houses 10 female elephants – it doesn’t take males at this time. It has room for six more, but it’s surprisingly difficult to obtain new elephants. After all, elephants are money makers for circuses and zoos, which are often loathe to give them up. This is why the sanctuary is never sent young elephants: the younger the elephant, the bigger the jackpot. In an attempt to create bridges between the circus or zoo world and the sanctuary, the staff say their elephants are “retired” – not “rescued”.

The sanctuary has no interest in breeding on the site. “We’re not breeding for animals to live in captivity,” says CEO Janice Zeitlin. “And this is captivity.”

Some of these elephants have harrowing stories. Sissy, stolen from the wild in 1969, survived a flood in Texas in 1981, spending 36 hours submerged under water with just her trunk above the surface. For years she was terrified of water, but after coming to the sanctuary she started wading in pools again.

“This is what the sanctuary is about,” says Zeitlin. “These celebrations. These milestones.”

Some elephants arrived with self-mutilation behaviours, such as biting their ears or tusking their own legs. “It’s a coping mechanism, and a lot of that is based on stress,” explains DeYoung.

I spend the day at the sanctuary with remarkable women. DeYoung moved across the country to work here. Zeitlin came 20 years ago and today runs the place. Sands Eaker worked up to the day she gave birth to twins. She told me she sometimes feels she knows the elephants better than her own children. This is not a job for them, it’s a calling, a devotion, a love.

I wonder if they are aware of the similarities between them and the elephants they care for. On the one hand, we have a highly intelligent, empathetic, deeply conscious species that has survived millions of years through a powerful matriarchal society. And, on the other, are the women of another species determined to give these pachyderm ladies the best years of their life, determined to do their utmost to heal the wounds caused by our sins.

Given that they are often taking in geriatric elephants – the youngest on site is 33 – workers at the facility have become accustomed to loss. In its 22 years, they have seen 17 elephants die. In 2013, they started a new policy of euthanising elephants when they felt they were suffering from irreversible health problems causing unrelenting suffering.

- An elephant grave at the Elephant Sanctuary.

“There was a philosophical change,” DeYoung says, noting that founders preferred allowing “nature to take its course”. The final decision comes down to the vets, but includes input from all the staff. Since 2013 they have humanely euthanised five elephants.

“We feel we are the stewards of this animal and it is our responsibility to take care of them – in life and in death,” adds DeYoung.

When death comes – whether due to euthanasia or other causes – the other elephants are allowed to spend as long as they need with the body. Elephants are buried on site and marker stones erected. Staff have observed elephants visiting the graves of their lost companions, especially those they were particularly bonded to. More then 10 years after Jenny’s death, Shirley still marches into the wood to mourn beside her grave.

Into the wild

But even if every zoo in the world was like the sanctuary, captivity can never replicate the wild.

Conservationists rarely consider the idea of releasing captive elephants back into the wild, but it has been done. Elephant Reintroduction, a NGO in Thailand, has reintroduced more than a hundred once-captive elephants into three protected areas since 2002. The work is challenging. Premjith Hemmawath, with the organisation, says mahouts had to teach one elephant how to drink water from the river instead of the tap. Still, many reintroduced elephants have thrived in this programme, with some even reproducing in the wild.

Fewer captive elephants have been released in Africa, but there are successes there too. Eight adult captive elephants housed in African countries (five males and three females) have been rereleased in Botswana. The most incredible example of reintroductions are Durga and Owalla, American circus elephants that were reintroduced into a park in South Africa in 1982. Both went on to have their own calves.

It’s expensive – that’s one issue. But the biggest problem, as Safina says, is that “there’s no place to free them to”. Asia is losing its habitat at record rates and surviving elephants are already coming into near-constant conflict with human populations. In Africa, the situation is even more dire due to unrelenting poaching. According to the Great Elephant Census, around 144,000 African savannah elephants have been lost in less than a decade in 18 African countries. But no one has even been able to count African forest elephants – a distinct species – which have taken the brunt of the poaching epidemic.

“Welfare is a concept that can be applied to any animal in any situation, not just wielded as a weapon to attack zoos,” said Fad. “Does anyone thinks that a starving elephant who just had her lower jaw blown off by a hakka pata [a makeshift explosive inserted in fruits and vegetables to injure or kill any animal raiding fields] takes comfort in her ‘wild’ status?”

Safina, who has spent a lot of time with elephants in the wild, adds that today wild elephants suffer from “more danger, stress, and harm … than do elephants who live in the better zoos, where they are comfortably bored”. Compared with the plight of wild elephants, he says, “captivity issues are a sideshow”.

What elephants would do

Before I left for Tennessee, I showed my six-year-old daughter a video about Shirley’s life. A 69-year-old Asian elephant at the sanctuary, Shirley survived a shipwreck, a truck crash and an attack by another elephant that left her crippled – her right hind leg forever-after bent at an irregular angle. I held my daughter as she wept through the video, but afterwards she brightened up and drew a picture for me to bring to Shirley.

I wasn’t sure I was going to see Shirley, though. The staff said she likes to wander deep into the forest, and she was the kind of elephant that would decide for herself whether to grace you with her presence.

In the afternoon, we find an Asian elephant, Tarra, and the staff proceed to give her a shower and feed her treats. But far away – just a large shadow-like shape deep among the tall Tennessee pines – stands another.

“That’s Shirley,” Sands Eaker tells me, adding that the crippled leg “doesn’t limit her. I’ve seen her climb some of the steepest hills – which I wouldn’t climb myself.”

We wait. And watching Shirley – just a silhouette in the forest – I feel that tinge – that pull – so many of us feel in the presence of an elephant, like we’re meeting a being both similar and alien, a great four-legged giant, a kind of demi-deity, a wise mother. Of course, it’s often a toxic intimacy: our desire to be close to elephants more often than not has resulted in their suffering and despair. We’re not elephants – and no human can replace an elephant for an elephant.

- The writer holds a picture of Shirley, seen behind him on the right, drawn by his daughter as a present to her.

But maybe our greater understanding of elephant needs will allow us to let them go – to let them be free again. To make sure captive elephants are living in places where they can be elephants again. And, for those in the wild: to stop slaughtering them for trinkets, to invite them to share this world with us unmolested.

“Oh, Shirley!” Sands Eaker exclaims.

And Shirley comes out of the forest to greet us.

I take a photo for my daughter – since the sanctuary is not open to the public she’ll never get to see Shirley herself – and I hope the image will be enough to impart that awe, that wonder, that reverence that radiates off these great beings. I hope it’s enough for my daughter, and all of us, to extend our empathy to a species alien to ourselves.

After all, that’s what elephants would do.

* This year’s World Elephant Day includes a march in Washington DC, a fundraiser at Chester zoo to combat elephant disease, and a special event at the Elephant Sanctuary’s new outdoor classroom in Hohenwald, Tennessee.